UPDATE: An expanded version of this article is available as a free eBook: ICE Prioritization Done Right

ICE (Impact, Confidence, Ease) is a popular idea prioritization method that has lately been getting some bad press. Some people openly warn against it as the worst thing you can do to your product. In this article I’ll explain why I think ICE is still a critical tool in the PM arsenal, and how to avoid pitfalls and misconceptions.

Quick Refresher – What is ICE?

ICE scoring, invented by Sean Ellis, is an evolution of the classic impact/effort analysis.

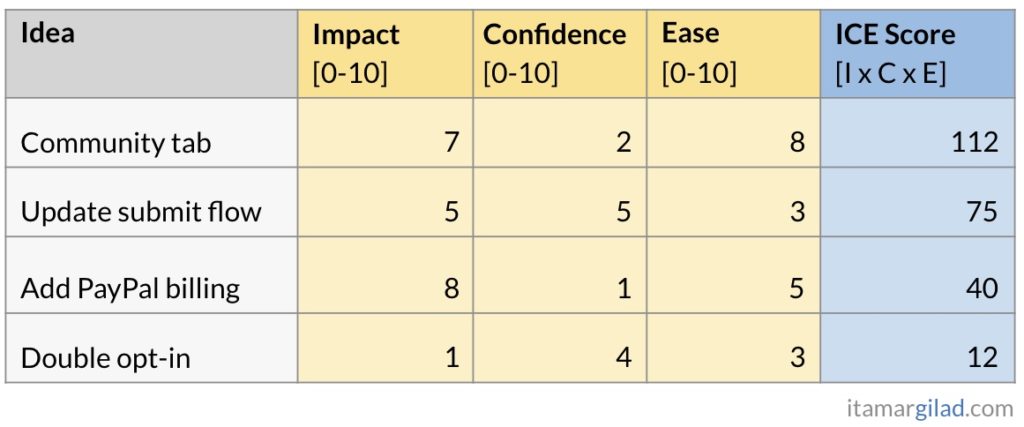

For each idea we need to assign three values:

- Impact – how much does this idea stand to improve the key metric we want to grow. I explain below what this key metric is.

- Confidence – how sure are we that we will have this impact? Another way to put this— how strong is the evidence in support of our impact assessment. I created a tool to help with this calculation — The Confidence Meter.

- Ease – how easy is it going to be to build and launch this idea in full. Usually this is the opposite of person/weeks.

Each value is in the range of 0-10. We multiply the three, or average them, to get the ICE score. The scores themselves are meaningless. They’re just a way to compare ideas. Sorting ideas by ICE scores gives us an order of priority.

ICE scores are not exact science. They’re just a hint— knowing what we know now, these are the ideas that look most promising. ICE does not guarantee that these are the best ideas, or that they will even work.

Why Do We Need ICE, Then?

Because of this reality:

- There are always more ideas than we can or implement or even test

- Only a small subset of these ideas will create positive outcomes

- We are bad at picking good ideas from the bad ones. The decision is often based on opinions, biases, egos, and politics.

- We tend to waste a lot of time in prioritization debates, just to end up with unreliable decisions.

ICE changes the dynamics by focusing the discussion on three questions: what’s the potential contribution to our goals (Impact), potential cost (Ease), and supporting evidence (Confidence). This shortens debates and makes them much more grounded. Less opinions, more evidence. We’re not guaranteed to make the best decision, but we’re improving the odds.

Can We Really Trust ICE Scores? Aren’t These Just Guesses?

Yes, Impact and Ease are always estimates. That’s why ICE has a third component — Confidence. It reflects how much we should trust our estimates (especially Impact where there may be a huge margin of error). The more we test the idea the higher the confidence value will be.

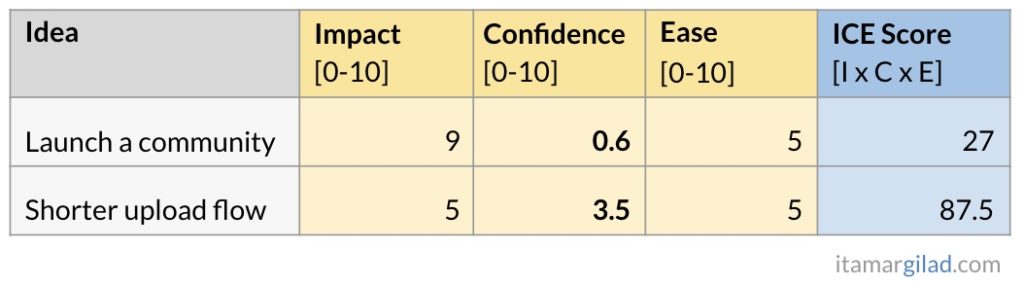

Here’s an example. Let’s assume you’re considering two ideas of a similar cost/ease: 1) launching a product community for your product, and 2) shortening the Upload flow. The community idea looks very promising—communities are all the rage now, and we estimate the community will get users to come back and engage more. The Upload Flow has a more moderate impact, but it has come up a number of times as a request from users, and initial tests show a good improvement in your key metric.

Which should you pick?

According to ICE, if you can pick only one, you should opt for shortening the upload flow. That’s mostly down to the fact that you have a lot more evidence in its favor. The very high impact that we assigned to the Community idea is based mostly on opinions and on market trends/buzzwords. These are very unreliable forms of evidence, hence the low confidence score. Importantly ICE doesn’t say you should dump this idea, just that you should test it further before committing.

In other words, ICE protects us from investing in ideas that are purely based on guesswork and promotes ideas that are supported by evidence.

We’re practicing ICE scoring in-depth in my Lean PM workshops. Join the next public workshop, or arrange one for you team.

Wouldn’t ICE Just Pick Safe, Easy Ideas?

This is a common concern. People fear that ICE will drive them towards some local optimum and miss out on big innovations. Here are some points to consider:

- ICE favors high-impact, easy to implement ideas that have strong evidence behind them. I argue this is the correct bias. It helps combat the big project fallacy.

- Following the ICE order should improve the odds of driving more impact, at lower cost. Do you really care if you achieve this by launching one, big idea, or five medium/small ones?

- The ICE priority order is just a recommendation. You should apply judgement. It’s okay to occasionally boost a low-ranking idea because you see potential in it. It’s okay to skip the top idea because it’ll create an internal political issue.

- The most important thing is to test ideas at a high rate. The more you test, the more ideas will get a chance, and the higher the probability of finding those rare good ones.

- Very big, high-risk ideas should go into a separate strategic track, with different resource allocations.

When Should We Use ICE Scores?

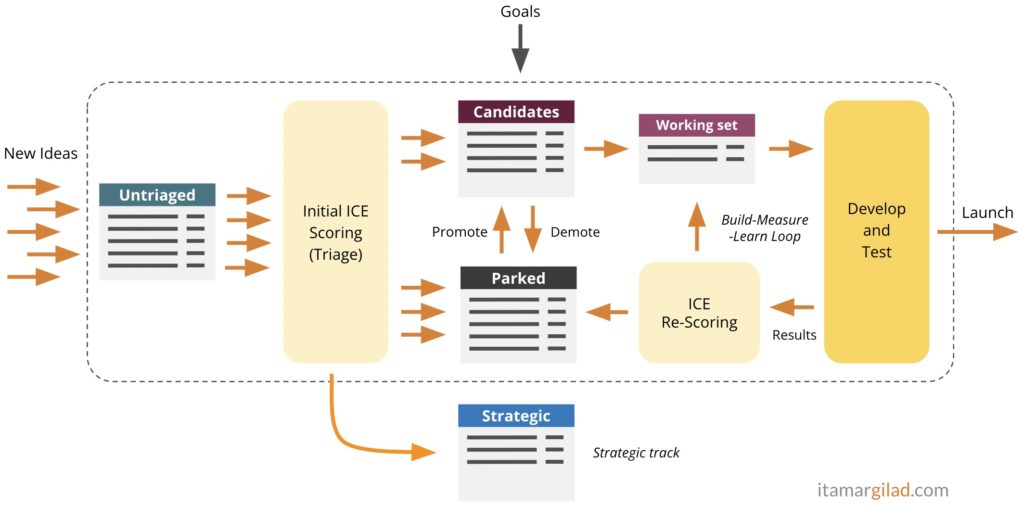

I argue we should calculate ICE scores:

- When we’re looking at a new idea (triage)

- When we’re choosing ideas to work on (filtering)

- When we find new data/evidence pertaining to an idea (learning)

- Periodically, when we’re reviewing our idea banks against the goals (maintenance/hygiene)

Think of ideas as you think of bugs. There are always many of them (and they keep coming), but only a subset are worth the investment. It’s important to continuously evaluate ideas and place them in the right bucket. Like with bugs, lack of proper hygiene can lead to massive backlogs of stale ideas.

One way to manage idea states is to move them between idea banks.

These are common idea banks types:

- Untriaged – new ideas that came from research, management, customers, the team, analytics, brainstorms, and anywhere else.

- Candidates – The most promising ideas we have at the moment, typically no more than 30-40. From time to time we should go over those and demote ones we feel are less relevant into the Parked idea bank.

- Parked – ideas that we feel don’t make the cut. This idea bank can be as long as needed and hold ideas indefinitely. It’s good to keep even what seem like bad ideas, in case they remerge. Then we can quickly look at our previous assessment and test results. It’s good practice to go over this idea bank every few months to remove duplicates, and see if there’s anything we now feel deserves to be promoted to Candidates.

- Working-set – A small, temporary set of ideas we’re working on in this goal cycle. A typical scenario is to pick 3-5 ideas per key result in our OKRs.

- Strategic ideas – ideas that take us outside our core business or are very large. We need to process these through our strategic track, which may have different goals and different resources.

This article was first published on my newsletter, where thousands of product people get free access to my articles, eBooks, and tools. Join here.

What is The Key Metric We Calculate Impact Against?

Each idea bank is prioritized towards a particular metric (this is the Impact component). Our Candidates idea bank should be ranked against a consistent, long-standing metric, ideally the North Star Metric of the company or division (teams working on monetization can use revenue or other top business metric). A Working-Set may be ranked against a quarterly key result. Strategic ideas may be ranked against metrics coming from our strategic goals.

Doesn’t This Take a Lot of Work and Time To Do?

It definitely can, although I’d argue far less than repeatedly developing the wrong ideas.

This is by far the biggest weakness of ICE—it requires persistence and repetition. This means someone, usually the product manager, will have to invest time. People who use ICE once per idea and never clean their idea banks will get very little benefits.

Here are some tips on how to shorten the time investment:

- During triage of new ideas, use shallow assessment— guesstimates, quick back of the envelope calculations, easy data lookups etc. Try not to spend more than a few minutes on each idea.

- Go deeper on your candidates – analyze available data, consult with team leads, stakeholders and experts, deeper business modeling. Then, with the most promising ideas, start testing.

- Don’t do it with the entire team – Empowerment and democracy are important, but ICE is not the place. The product manager should own ICE scoring, but must do it very transparently, and should be open to feedback and questions. You may triage ideas with team leads, but leave the team, stakeholders and managers out of it—you’ll be saving them a lot of time. You can involve the team in choosing which ideas to pursue further.

- Don’t turn the Idea banks into suggestions boxes. Anyone is welcome to propose an idea, but best if they approach the PM for that. The PM on their part should strive to say Yes (i.e. we will consider this idea) to all but the clearly out-of-scope or clearly unethical ideas.

- Put pure engineering ideas in a separate bank and let the engineering lead prioritize them.

Why Do We Need Idea Banks?

Multiple reasons:

- To store ideas for as long as needed. For example when someone gives us an idea, we don’t have to reply with an immediate Yes or No. We thank that person and can put the idea in the untriaged idea bank. Later that person can follow the idea through its voyage.

- Idea banks remind us to think holistically. There’s always more than one idea. As we get momentarily excited about idea X, the idea bank will help us see how it compares.

- Surface clusters of ideas – these sometimes indicate a theme or a hidden goal, or they may just show that our thinking is limited to one particular area (promotions? notifications?) and that we need to think broader.

- To help us find duplicate ideas, and to recall past evaluations and test results when an idea resurfaces. An idea bank is actually our knowledgebase of learning.

- To give us a realistic sense of how much we stand to improve our key metric. If all we have is weak ideas, we should go and do some research and brainstorming to uncover more.

What Happens When We Test an Idea?

I argue that every time you test an idea, you should rescore it. This practice helps us implement the “Learn” part in Build-Measure-Learn. If you do this repeatedly, most of your tested ideas will end up in the Parked idea bank and some will be launched.

Here’s a full example of how to combine ICE with testing.

Should We ICE Everything? What About Must-Have Features?

Yes, I feel you should ICE every product idea you plan to launch independently (but not every individual product/design decision – that’s impossible).

Here’s why I think there’s almost no such thing as must-have features.

Wouldn’t ICE Miss Some Good Ideas (False Negatives)?

For sure, but so will human judgement and any algorithm you can come up with. 100% accuracy is impossible. We’re looking to (greatly) increase the odds of success compared to what we use today, while reducing the time spent on debates and idea competitions. The odds will improve even more if you test more ideas quicker.

What’s the Difference Between ICE and RICE?

RICE is a derivative of ICE invented by Intercom. It adds a fourth component — Reach — how many users/customers will be impacted. Many ICE practitioners, me included, argue that Reach is simply a component of Impact, and not necessarily a component you always want to factor. For example, an idea that only impacts a small, but very highly-engaged subset of users (power users) can be of high impact although it’s low in reach.

Can We Really Trust a Spreadsheet to Make the Decisions?

Shouldn’t We be Using User Research Instead of ICE?

Doesn’t ICE Focus Us on Solutions Rather Than Problems?

These are some common arguments against ICE I’m seeing on social media. I understand the concerns, and partly share them. However, I feel these are strawman arguments — they go against an overly-simplistic interpretation of ICE (which unfortunately some companies actually practice).

In this version of ICE people just invent ideas, ICE-score them, and then build and launch whatever ICE tells them to launch. They don’t do research, don’t focus on the users and their needs, and don’t apply judgement. It’s a kind of soleless, borg-ish approach to product development.

Of course, at least for me, this is not at all how you should use ICE:

- First, if I haven’t made this clear yet: ICE only helps if you do research and testing. It’s not in any way a replacement. They’re all part of a larger system.

- ICE doesn’t say how you should come up with ideas. User research is a great source, but of course there’s also market research, data analysis, observing trends etc. Invented ideas are okay too, but they’ll usually come with low confidence because they’re based on opinions.

- ICE optimizes for the goals. If the top metric is centered on user/customer value, as I think it should, then ICE will select customer-focused ideas.

- Qualitative user research techniques (interviews, observational studies, usability tests, etc) are invaluable sources of opportunities, ideas, goals, and evidence. All product teams should use them. However they are not prioritization methods. You can’t launch one of those every time the VP of marketing dreams up a new feature. ICE is a prioritization technique and it’s very easy to combine it with qualitative and quantitative research – I’ve seen many teams happily doing just this.

- ICE is the friend of researchers. It motivates teams to find better ideas and to collect stronger evidence.

What’s The Bottom Line?

- Use ICE to bring consistency, transparency, and realism into your idea prioritization

- Combine it with research and testing to greatly improve the odds of success

- Be prepared to spend time on an ongoing basis, but it will pay dividends and get easier with practice.

- Don’t worry about all the negative hype. Make up your own mind after you’ve tried it.