The Net Promoter Score is almost an industry standard. We’re constantly bombarded with the question “How likely are you to recommend company X or product Y”, and most companies I meet, including ones I consider to be very good at product, use NPS surveys in some way. But NPS is also quite divisive — while some people swear by it, others see it as harmful. I usually don’t critique methodologies I don’t use, but the Net Promoter Score is so dominant that I feel it deserves deeper research. In this two-part series I’ll share what I found. I’ll go over the history and research that led to the invention of the NPS, as well as the counter-research and reasoning that oppose it. I’ll explain what I think makes NPS a very iffy metric, and suggest some ways to improve it.

Recap – The NPS Survey

We’ve all seen them, but here’s a quick recap of what the NPS survey includes:

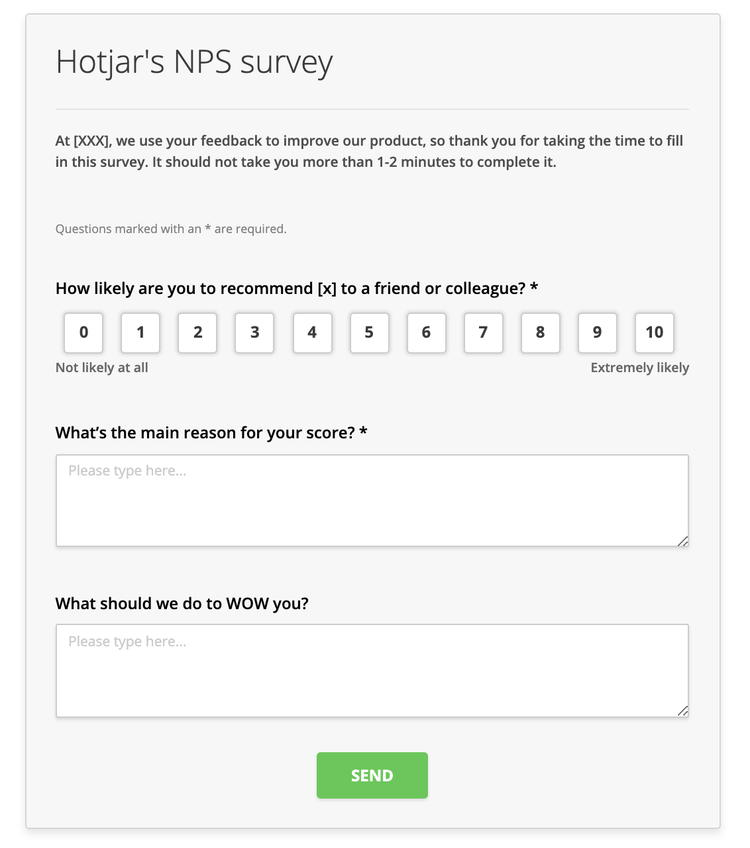

- A question: “How likely are you to recommend [X] to a friend or a colleague”

- An 11-point scale ranging from 0 to 10, sometimes with the labels “Not likely at all” and “Extremely Likely” for 0 and 10.

- A bucketing of responders into:

- Deatractor: 0-6

- Passives: 7-8

- Promoters: 9-10

- The NPS metric: NPS = %Promoters – %Detractors. Scores fall in the range of -100 to 100 where higher is better.

- (Optional) One or more open questions like “What’s the main reason for your score?”

I learned there are big open questions about all of these parts. The NPS metric is perhaps the most problematic.

The Origins of the Net Promoter Score

The Net Promoter Score was first introduced in a 2003 Harvard Business Review article called The One Number You Need to Grow, written by NPS inventor and Bain and Co. partner, Fred Reichheld. Reichheld is an expert and proponent of the concept of customer loyalty. He had written a number of books on the topic prior to publishing the article.

As the title suggests, the article calls out NPS as the most important business metric for any company. According to Reichheld, the most important customers are those that recommend the product or service to others (Promoters). Reichheld attributes both growth and profitability to promoters, despite earlier clearly explaining that retention, not recommendations, is the key driver for both. He then adds a third benefit of promoters — free marketing. This somewhat convoluted logic culminates in broad pronouncements:

The only path to profitable growth may lie in a company’s ability to get its loyal customers to become, in effect, its marketing department.

[E]vangelistic customer loyalty is clearly one of the most important drivers of growth […] in general profitable growth can’t be achieved without it.

The One Number You Need to Grow | Fred Reichhert, HBR (2003)

The article describes two studies to back these claims up:

- Reichheld and his team sent a 20-question survey to customers of 14 companies across six industries. They found that the question “How likely is it that you will recommend company X to a friend or a colleague” best correlated with the purchase behavior of the customers (as provided by the companies) as well as with the number of times they actually recommended (as self-reported by the customers).

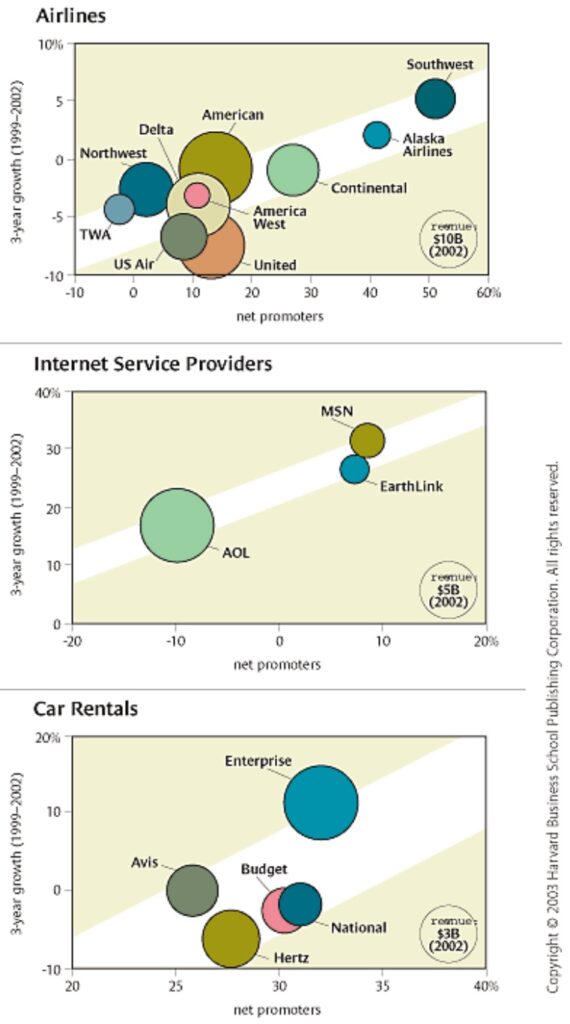

- The measurement company Satmetrix, who co-owns the trademark for NPS and on whose board Reichheld sits, conducted a large-scale NPS email survey across 400 companies in more than a dozen industries, gathering “10,000-15,000” responses. The researchers calculated the aggregate NPS score of each company and plotted those against the companies’ revenue growth, presumably taken from public filings, over a three-year period from 1999 to 2002 (incidentally the years of the burst the dot.com bubble and the recessions that followed). They found “striking results” —“this one simple statistic seemed to explain the relative growth rates across the entire industry”.

These two pivotal studies that had transformed the landscape of customer measurement were never published in full detail, nor subjected to peer-review. The data used by Reichheld and Satmetrix was not made public either.

The rest of the article is devoted to case studies that explain (in hindsight) the success and failure of certain companies in terms of % of Promoters vs. % Detractors. There’s a fair bit of hyping of the NPS metric and downplaying of other metrics (including retention values).

Reading through Reichehld’s 2003 article it’s hard to shake the feeling that the Net Promoter Score was designed first and foremost to be highly sellable to big-corp execs. Reichheld and his colleagues devised one simple metric — a score in the range of -100 to 100 — that is easy and cheap to measure, and yet can “accurately predict” future business growth. They clearly had a good goal in mind — to help executives embrace the core principle of customer-focus. To to do the job they invented a methodology no CEO will be able to say no to.

Good intentions aside, the article aggressively sells NPS as the one and only customer-focused metric, while downplaying any potential “competitors” including customer satisfaction and retention metrics. With the benefit of further research we know many of the claims made in the article could not be reproduced. Inventing a too-good-to-be-true model and overselling it is definitely not unheard of in business management consulting, however in this case the marketing succeeded far beyond anyone’s expectations.

In my Lean Product Management courses we practice using principles, frameworks and tools that bring modern product management thinking into any org.

Secure your ticket for the next public workshop or contact me to organize an in-house workshop for your team.

Reception of NPS

The combination of logic, science, and superlatives made the Net Promoter Score article an industry must-read. The timing was also impeccable. Malcolm Galadwel’s best-seller The Tipping Point had turned Word-of-mouth and Virality into the hot buzzwords of the moment — the secret sauce to success in the Internet age (not unlike “gamification”, “habit forming”, and others that came later). Reichheld further amplified the message in articles and in a 2006 best-selling book.

As a consequence NPS caught on like wildfire. In the following decade two-thirds of Fortune 1000s reportedly started using NPS (according to Fortune magazine the ratio today is three quarters). In earning calls multiple CEOs presented NPS as a game-changer:

“Net Promoter gave us a tool to really focus organizational energy around building a better customer experience. It provided actionable insights. Every business line [now] addresses this as part of their strategic plan; it’s a component of every operating budget; it’s part of every executive’s bonus. We talk about progress on Net Promoter at every monthly operating review.”

Steve Bennett, President & CEO, Intuit Inc.

The tech industry followed the trend. IBM, Microsoft, Facebook, Cisco, Sony, Logitech and other mega-corps started using NPS, but so did many smaller companies despite not being in the original target market for NPS. Net Promoter Score became part of the default company operating system that managers and investors consider mandatory. I even noticed that for some younger product people the term NPS has become synonymous with satisfaction surveys (“let’s run an NPS for the onboarding flow”).

Today however, no one seems to remember that NPS is supposed to predict growth and recommendations (which we now recognize are just one of many success factors). NPS is seen as a measurement of customer sentiment — how customers and users feel about the product or company (which I think is actually more realistic). A lot of attention is put on the metric itself, but it’s a number that’s very hard to act on (usually a red flag in metrics design) as customer satisfaction is affected by a variety of factors and isn’t very deterministic. The only actionable, and arguably most useful part of the survey are the optional open questions at the end. So in practice many companies use NPS as a glorified customer feedback tool. That doesn’t make NPS necessarily bad, especially as long as you use other user metrics and other forms of research.

Criticism of the Net Promoter Score

The Net Promoter Score also has its fair share of “detractors”. The user researchers I worked with at Google were dead set against using NPS (we used a combination of usage metrics and a quarterly satisfaction survey), a sentiment shared by many in the user research community. User research and UX design expert Jared M. Spool wrote a full article entitled Net Promoter Score Considered Harmful detailing flaws in the NPS question, scale, and score calculation. I’ll touch on some of Spool’s points in the next article.

Data scientists also are not impressed with the Net Promoter Score. As I’ll explain in the next article, the way the NPS metric is calculated both leaves a lot of survey information out, and makes the metric more susceptible to random noise. This means you need large sample sizes to get to statistical significance, which makes the NPS metric impractical for A/B experiments, and less reliable for other types of statistical analysis.

Scientists have also expressed doubts about the research behind NPS. Attempts to replicate the results provided in the original article have largely failed. In this article Jeff Sauro of the research firm MeasuringU summarizes multiple studies who tried to correlate NPS with company growth. He concludes that at best there’s weak correlation (r=0.35). In most studies, including Reichheld’s original study, NPS correlates with historical growth rather than with future growth, i.e. it may be a good trailing indicator, but not necessarily a good predictor. There’s also very scant proof that the division into Detractors, Passives, and Promoters, as measured by NPS, accurately predicts future customer behavior.

Reinterpretation of NPS

Over the years the creators of Net Promoter Score have refined and softened the message. In more recent articles and books, co-authors Fred Reichheld and Rob Markey (also a partner at Bain and Co.) talk about NPS as a “system” or a “philosophy” for customer-centricity.

Big NPS is a philosophy of business that puts customers first. […] [I]t maintains that the only way to succeed and grow a business profitably (in a way that would make employees and investors happy) is to first make sure your customers are so happy that they are referring friends and returning. […]

Little NPS is a scoring mechanism.

Interview with Fred Reichheld, NPS creator | CXOTalk (2022)

The NPS System (which the creators of NPS will be happy to sell you) must include industry benchmarks (which they’ll sell you as well, although to be fair there’s now a much larger industry selling NPS solutions and benchmarks). Surprisingly it can also include other metrics, some of which may even be more powerful than the almighty NPS metric:

If that customer is coming back, giving us all their business, referring friends, that’s a promoter. I don’t need a survey to tell me that. I think many businesses still need surveys to augment the real behavior data. But that’s once or twice a year, and it’s an advanced agreement with the customer [emphasis mine]

The notion of 0 – 10 and it’s a survey, those are practical today. That won’t be the basis of this methodology in ten years.

Interview with Fred Reichheld, NPS creator | CXOTalk (2022)

The owners of NPS also acknowledge it’s not directly actionable:

The object of measuring a Net Promoter Score should not be focused on improving the score. Rather, the goal is to improve business performance by earning a customer’s repeat purchase, additional purchase, referral, etc.

Use the “summary” NPS statistic for reporting and motivation. But use alternative calculations and analytic techniques when performing A/B testing, significance testing, etc.

Rob MArkey | Medium 2017

Reichheld and Markey also strongly disapprove of what they consider overuse, misuse, and abuse of the methodology, especially the habits of bombarding customers with surveys and tying bonuses to NPS results.

[T]here are about a thousand too many survey requests out there today. It’s absurd. Companies who understand net promoter see that the real goal is the big NPS: How can I make sure that we’re creating more promoters and fewer detractors?

Interview with Fred Reichheld, NPS creator | CXOTalk (2022)

However it seems no one is noticing this new interpretation of NPS. Many executives, employees and consultants are still holding on to the more simplistic view of NPS as be-all-and-end-all customer metric pushed in the original article.

Takeaways

The Net Promoter Score is a methodology invented by management consultants for the benefit of corporate executives in the 2000s. Its aim was good: to reduce myopic focus on business results and usher a customer-centric mindset. As such, I have no doubt NPS did a lot of good for a lot of corporations.

However, through a combination of hype and market momentum, NPS has gained a status of one-metric-that-matters that it likely doesn’t deserve. This is especially true today when we have much more indicative metrics that are based on what people actually do, rather than what they say they might do. Using NPS isn’t necessarily harmful, but there are important discussions to be had on how trustworthy the metric is and whether it’s the best tool for the job. Check out my next article for a deeper look at the methodology to decide if NPS is right for you, and if there are ways you can use it better.

Continue to Part 2 of the series.

Join thousands of of product people who receive my newsletter to get articles like this (plus eBooks, templates and other resources) in your inbox.