It was mid 2004 and my colleagues and I were gathered in a cinema hall in Tel Aviv to hear our American CEO speak. The charismatic gentleman on stage was all smiles and positive energy. He told us he was proud of what we had achieved that year. There was one topic, though, that made him visibly unhappy. A few years earlier a competitor had launched a product into a market that we were playing in for years. We didn’t see this product coming, and it turned out to be a major breakthrough. Over the years the competitor acquired millions of loyal customers and a landslide of revenue and brand recognition.That competitor was Apple and the product was the iPod. I worked at the time at Microsoft and, as our CEO Steve Balmer pointed out, we had just missed out on a major opportunity, one of a few Microsoft will miss in the next decade.

Opportunity is a term that is thrown around a lot, but means different things to different people. The Merriam Webster dictionary elegantly defines it as “A favorable juncture of circumstances”. In tech, opportunities are favorable to our mission—delivering value to our customers and capturing value back. Most of what we build creates incremental value at best. Opportunities are those rare, often hidden, pockets of value that let us create step-function improvement or even exponential growth.

What are those circumstances that converge to create an opportunity? Here’s a partial list:

- Underserved user/customer needs (aka user problems, aka jobs/pains/gains) – e.g. I wish to take music with me on the go, but can only take 20 music tracks on the go, I’m working from home and I have too many video calls…

- High costs of competitor products – monetary or other

- New technologies – e.g. microprocessors, multi-touch, blockchain

- New market segments or new potential large customers – for example mobile photography enthusiasts (Instagram’s original market segment), or General Electric.

- New platforms, standards and APIs – e.g. the iPhone app store, HTML5, Whatsapp APIs.

- New partners and channels

- Mergers and acquisitions – e.g. a company that has the technology or product you need

- Market/economy/geo/political shifts – e.g. a global pandemic

When Apple built the iPod it was leveraging a new technology—Toshiba’s 1.8-inch 5GB hard drive, the massive pressure that peer-to-peer file sharing was putting on the music industry, as well as the untapped need to easily buy individual tracks and carry all your music with you in your pocket.

Some folks would argue that the only type of opportunities are those to do with customers’ underserved needs and desires. I encounter this line of thinking from time to time—everything must start with a “customer problem” and customer problems are the only thing that matters. Underserved needs/desires are indeed the most important type of opportunity, but saying that they’re the only one is narrow-framing the job of product companies and product teams. We definitely have to consider also opportunities for improving our business model, reaching out to more customers, making our system more robust and scalable, reducing costs, and so on. Business-value opportunities and customer-value opportunities are not mutually exclusive, in fact they often go hand-in-hand.

Threats

Opportunities have an sinister sibling—threats. Where opportunities help us deliver and capture more value, threats can push us back and impede value delivery/capture. Here too we tend to fixate on just one type—competitive threats—but there are actually quite a few (again, partial list):

- A competitor or alternative solution is entering our core market or blocking us from seizing an opportunities

- Technological limitations

- Code and design debt

- Security and privacy issues

- A partner/platform cutting us off

- New regulation

- A major customer threatening to leave

Threats can be just as important as opportunities. Consider this scenario. You receive a warning from the app store that accounts for most of your app downloads that your app is not complying with its new policy. You have 45 days to fix the app or have it be removed from the store. That is a threat, and it’s probably more important than any customer need or business opportunity currently on your plate.

Discovering Opportunities and Threats

This is a broad topic that requires its own article (or book), but the general guideline is to (metaphorically) get out of the building. Opportunities and threats almost always lie outside your organization. The companies that are most often surprised by missed opportunities (as we were in Microsoft) are the ones that assume that they already know all there is to know.

Here too there’s a common misconception: the only way to discover opportunities is to observe customers, interview them, and build empathy. I’m a strong proponent of qualitative user research and I strongly recommend all product teams to practice it. However a lot of important insights can come from quantitative research—analyzing usage data, running surveys and smoke tests and so on. We must use both to avoid false positives and false negatives.

Besides the users and customers, we want to observe trends and inflection points in the market, technology, adjacent markets, the economy, and generally anything else that might be pertinent to our mission. Paul Graham once said that “The best ideas come organically from noticing things.” The same is true for opportunities.

A lot of opportunities are discovered by building things. A team at Gmail once built a lab (optional feature) that automatically added labels like Notifications, Bulk and Personal to messages. It was far from perfect, but it taught us that people find value in this sort of classification because it helps them deal with the influx of low-importance mail. This led to Gmail’s tabbed inbox that sorts email into Primary, Social, Promotions and Updates that helps exactly those users. Before you stone me as a solution-focused heretic you should realize that pure research can take you only so far, and that today we don’t have to build a full product (or even write software) to start learning. We have many, cheaper validation techniques.

Strategy

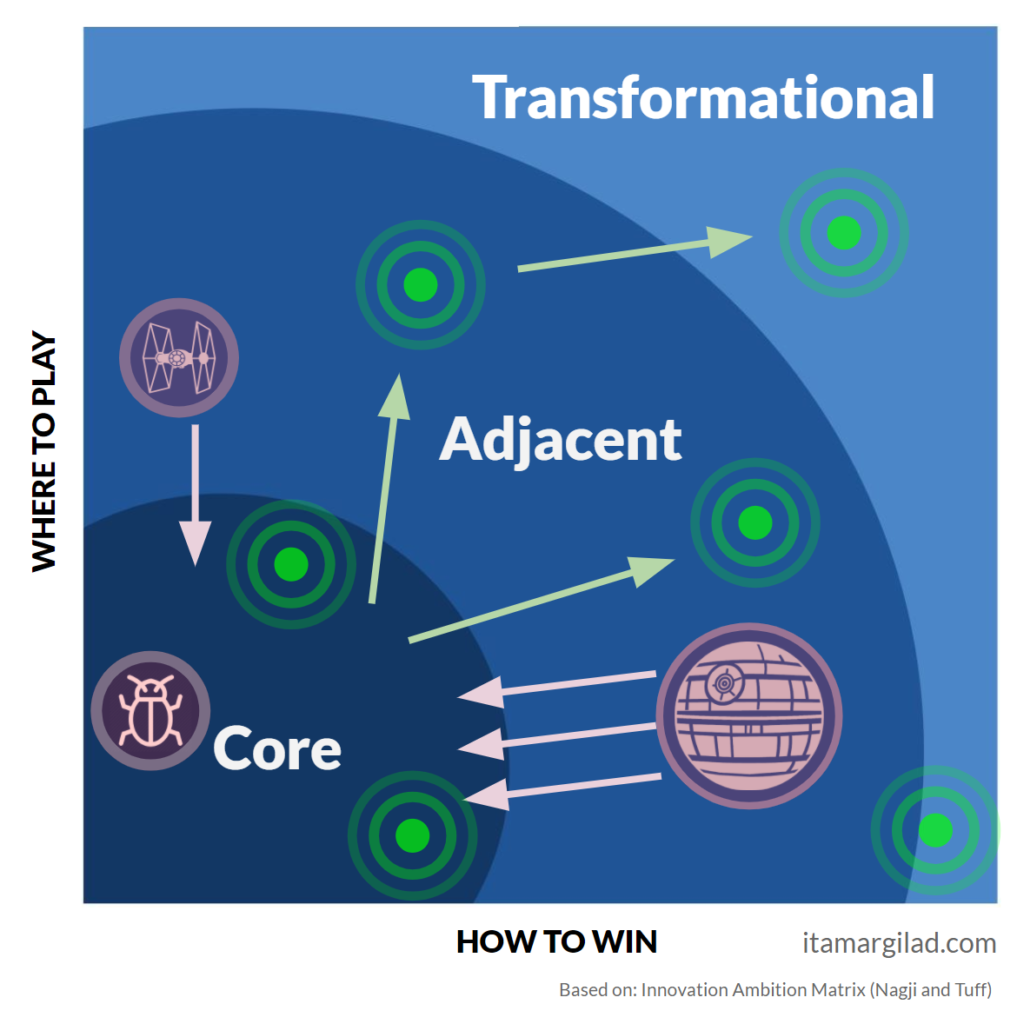

Opportunities and threats are the building blocks of our strategy. One way to visualize this is to map them onto Bansi Nagji’s and Geoff Tuff’s oddly named innovation ambition matrix that splits our strategic initiatives into Core (current market, products and technology), Adjacent (markets, products or technologies that are new to us, but not far from what we’re doing) and Transformational (markets, products or technologies that are new to us and quite unrelated to what we’re doing). If the matrix is your strategic radar, then opportunities and threats are blips on the radar screen.

To demonstrate how this works consider the example I started with. Apple made a transformational strategic move with the iPod. It transformed Apple from a company specializing in high-end personal computers, to a lifestyle consumer brand. This move paved the way to the iPhone, iPad, and Apple Watch. Microsoft saw handheld devices as an adjacent opportunity, expanding its core (Windows, Office) into new platforms.

Evaluating Opportunities and Threats

Opportunities and threats are theories. It’s very easy and very wasteful to fixate on non-real ones. In the early 2010s Google fixated on social networks (especially the threat it saw in Facebook), leading to Google+, and largely missed the opportunities presented by social mobile apps like WhatsApp and Instagram.

The thing to do is to constantly be on the lookout for potential opportunities and threats, to collect them and to evaluate them. We can size opportunities and threats on paper, but that’s a far cry from proving that they’re real. Ranking opportunities is important, but don’t let anyone tell you that they have a bullet-proof method to do it.

Business consultants will be happy to teach you a variety of strategic analysis tools such SWOT, PEST and 5 Hats. I feel that those are designed for more traditional industries, but it’s possible you’ll find value in them.

More commonly used tools are Alex Osterwalder’s and Yves Pigneur’s Business Model Canvas. For startups I recommend Ash Maurya’s Lean Canvas. For feature opportunities that don’t create new products or business models have a look at Jeff Patton’s Opportunity Canvas. (yep, we love canvases in our industry).

In my mind though the best way to validate an opportunity is to put it to the test by running in cheap experiments. Most opportunities and threats will turn out to be non-real, but some will seed our future products and features. I’ve written a whole article on how to discover your strategy using this method, which I call multiple strategic tracks (MuST). It’s a pattern that many market-leaders have used to great effect.

Acting on Opportunities and Threats

As you may know I’m a big proponent of the GIST framework (Goals, Ideas, Steps and Tasks) as a way to turn strategy and into action. GIST is a system I started using at Google and further enhanced over the years based on work with my clients.

So here’s what I suggest you do: size the opportunity/threat and/or validate them until you reach the point that you feel fairly certain that you should park it or act on it. If it’s the latter you have to choose whether to turn the opportunity/threat into a goal, or a set of ideas. Then let the GIST process do its thing. GIST will lead you to develop the best solution to address the goal using iterative development and testing of multiple ideas. Sometimes the process will help you discover that the opportunity/threat isn’t as important as you though. However you may encounter yet new opportunities and threats (this is very common) which you can add to your opportunities and threats bank.

Let’s look at a few examples.

Let’s say you’ve determined that some of your potential users are not able to use your mobile app because they’re suffering from irregular Internet connectivity. If you decide that this is a top priority issue that you have to solve, you can create a goal—users with choppy Internet connections can use the service—and affix outcome metrics to it to indicate what success looks like. If, on the other hand, you think that making the app work under choppy Internet connections is not a must-have, it’s only one way to address a bigger goal, for example drive growth in emerging markets, then you can add a few relevant ideas to your idea bank and evaluate those against others ideas.

As another example let’s say that you receive that warning from the app store that you have 45 days to fix the app to comply with the new policy or have it be removed from the store. In this case you should turn it into a goal and start generating ideas on how to comply with the new policy. Lesser threats, say a competitor launching a feature that might be interpreted to be superior to yours, can be turned into ideas or parked.

I intentionally didn’t bake opportunities and threats into GIST. They are important, but I feel that assessing and validating them is a separate, and much slower, process. Nor do I see a need to connect every product idea to an opportunity or threat—that’s a bit of plumbing that I feel isn’t really necessary in many cases and will mostly creates overhead. It may also bias the system. Ideas should be evaluated on their own merit, not on the merit of a theoretical opportunity or threat. Having ideas connected to customer-centric goals is a much better approach in my exprience.

Life is Not That Simple

I feel a lot of companies are mishandling opportunities and threats, and ending up with suboptimal or even destructive strategies. This is a big and complex topic that’s hard to do justice to in 2000 words , and even harder to address with an elegant framework. If there’s one idea I suggest taking out of this article is that you should use a wide gamut of methods to discover, evaluate and test opportunities and threats and, as always, you should stay healthily skeptical of the opportunities and threats you find as well as of the framework you use.