Working with stakeholders can be tough. Whether it’s sales, marketing, PR, legal, or finance, these folks tend to have strong opinions about the product, and they are often more senior or more influential than you. They certainly are better at negotiation, escalation, and corporate politics. Your company is probably not offering good tools to deal with this situation, and your manager will prefer that you resolve it on your own.

Here are three approaches that worked for me over the years.

1. Make Them Your Partner

It’s really important to understand that you don’t “manage” stakeholders, and they don’t manage you. They are certainly not your customers, nor is their job just to sell, market and support what you build. Much like with engineering and UX, the relationship is one of partnership.

What does partnership mean? It’s an exchange of value. I help you and you help me. Helping them is not the same as building whatever “deal closing” feature they have in mind. You need to figure out what they’re really optimizing for. Making their numbers? Pushing some big initiative? Protecting against a major threat? Understanding the motive will help you find other ways to help beyond what they’re asking for.

But you have an agenda too — to discover and build the product that will create most value for the customers and the company. Your stakeholder may not know that. They may come from a background where product works in the service of the business. So you have to explain what you’re trying to achieve, and what you need from them: autonomy, support, peace of mind, access to customers, data, or whatever else. Your stakeholders understand give-and-take and will be willing to support you as long as they know that their interests are served.

But it’s not just a business relationsionship. Closely partnering opens the door to mutual understanding and appreciation, and sometimes even to friendship. Then you’re on a whole different level of colaboration.

Here’s an example: my first job as product manager was in a company that sold communication software to embed in voice and video products. The product was highly technical and the sales reps often needed someone with deep knowledge to talk to customers and help close deals. Realizing this I joined many pre-sale meetings in APAC and EMEA. During these trips I got to know the sales reps personally, and I also saw first-hand how hard their job was. We had discussions about the bigger picture of the product, and what’s happening in the industry. These trips usually ended in success — I learned a lot about customer and sales needs, and deals were signed quicker. They also helped forge a strong partnership with the APAC and EMEA sales teams. These folks were generally supportive of my product decisions, and weren’t overly demanding with customer requests. They trusted me to PM the product, because they knew I had their needs at heart.

The same was not true for the North America sales office. I didn’t spend as much time with the local team there and consequently I didn’t fully understand their situation, which was different and more competitive. On their part, they didn’t trust the product and invested less in selling it. The relationship was always tense and the team was generally demanding and critical of product decisions. Behind the scenes they complained that the product was the reason they weren’t making their numbers. This cast a big shadow on what otherwise would have been a clear success. It also drained a lot of the joy out of the work.

The bottom line is this: never work in an “us against them” mode. Forging a partnership and getting everyone on the same side is paramount.

2. Be Explicit and Persistent About Your Goals

If your OKRs are a list of features you’ve committed to deliver this quarter, you’re sending a clear message: we’re a feature factory, and whoever presses hardest will get their favorite features in (or keep their least favorite features out).

Outcome goals send a very different message — here’s what we’re trying to achieve. The goals communicate an important truth — we’re not just aiming to make quarterly numbers. While a product team can have business-support goals (“Increase conversion rate to Y%”), they also need to deliver value to customers, to maintain system health, and to work towards strategic goals. Involving stakeholders in the quarterly goals discussion (without slipping into the how) is a good way to help them see the full breadth of what the product team aims to achieve and to create shared context. It also drives home the fact that product teams can’t do everything for everyone.

Another important recognition is that there are no “business goals” vs. “product goals”. We’re all working towards the success of the company, which heavily depends on creating customer value. Tools like the North Star Metric, Top Business Metrics, and metrics trees help visualize the relationship between customer value and business value, and create shared context as well as shared goals. For example “improve activation rate” is a goal that neither marketing nor product can own alone. It has to be a shared goal.

Once the goals are set, be very persistent about sticking to them. When someone tries to push a new agenda, pull out the goals and remind them that’s what we agreed to focus on. When someone proposes a new must-have feature, show them how their idea compares to others in terms of contribution to the goals (ICE analysis can help a lot here).

3. Use Evidence

Many PMs fail to stand their ground because they use opinions rather than evidence. Everyone has opinions, and in a battle of opinions the more senior or more influential person wins. If you want to be on equal footing, you need to introduce the concept of evidence into the discussion.

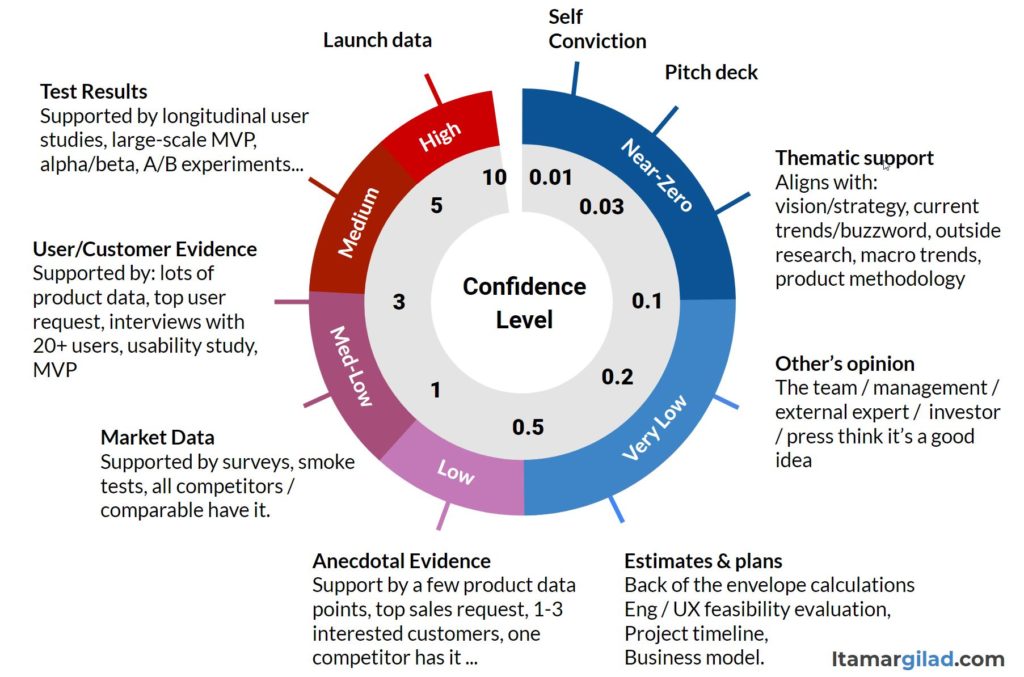

Evidence is an ambiguous term. Many people confuse weak evidence (“one competitor did this”) with strong evidence (“Early adopter customers are using the product as we expected”). Some stakeholders may believe that their opinion is evidence enough because they’re “the voice of the market”, so any idea that feels right to them must be a good idea.

For these reasons I created the confidence meter.

Companies that use the confidence meter start asking two important questions: “What evidence do we have that this idea will work?” and “How strong is this evidence?” Using the tool reveals a sobering picture — many decisions are based on opinions and weak evidence. This helps promote a more experimental and data-driven mindset. Stakeholders are not averse to this approach, simply because they see a lot of opinions-based, handwavy decisions coming from the side of the product.

The Bottom Line

Your stakeholders are smart, rational people that bring important information and concerns. The classic approaches of appeasing stakeholders, negotiating them into a compromise, or simply disregarding what they say, are very suboptimal. Your job is to get everyone into a place of true collaboration with broad shared context and clear goals. You should solicit the help and feedback of your stakeholders when you create your (outcome) goals, but then ask them to give you room to try out multiple ideas. When you make decisions, back them by evidence, and share broadly. If you do this, you’ll get a lot more trust, backing, and freedom to act. That will also free your stakeholders to focus on what they do best, which is definitely not making product decisions. Even if it’s not immediately apparent, that’s what they wish for too.

To learn how to put this approach to use and create high-impact products, join one of my upcoming public workshops, or message me to arrange an in-house training or keynote.

Photo: Warner Bros.