When talking to product managers, company leaders, and customer-facing folk, a common belief surfaces: if enough customers (b2c), or an important customer (b2b) ask for something, then we should build it. This axiom is reflected in prioritization discussions as well as in many product management tools that rank ideas by “customer votes”.

Customer feedback, whether it comes from feedback tools, interviews, surveys, sales calls, advisory boards, or any other means, is extremely important. We want to stay attuned to what’s important to our customers, and to satisfy their needs; the success of the company depends on it.

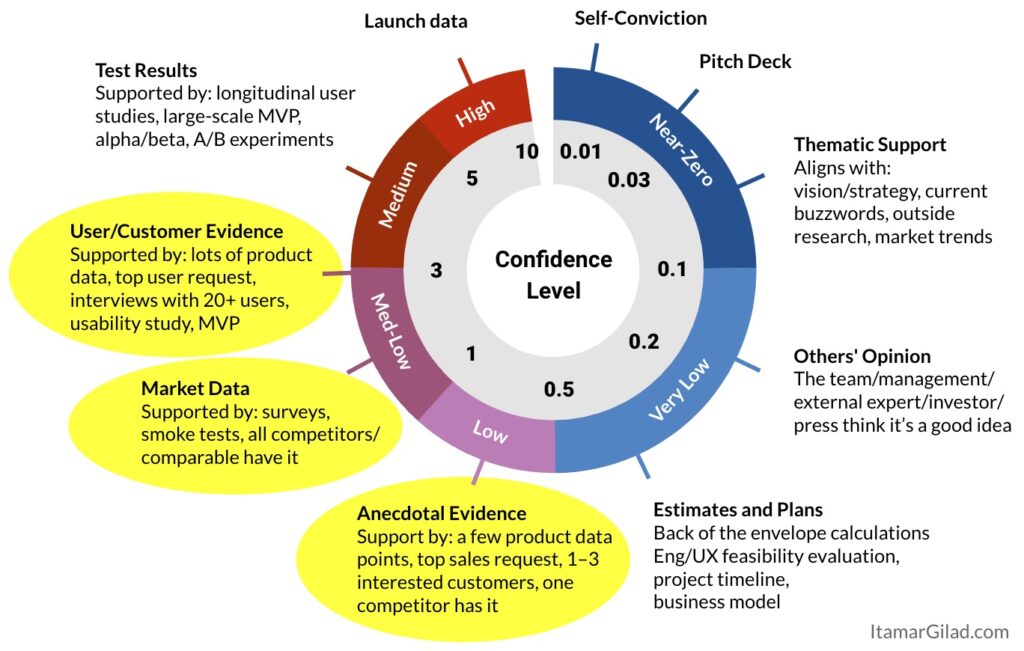

But that’s not the same as assuming the customer is always right. Modern evidence-guided companies take a measured approach to customers’ input; It is collected, processed, and reviewed, but, as my Confidence Meter reflects, it is not considered strong evidence:

Sporadic customer requests count as Anecdotal Evidence, and create only Low Confidence in the proposed idea (if you sell to large enterprises you can give this type of evidence x 2-3 confidence boost, or count how many sub-groups within the customer org asked for this). If customers express support for the idea in a survey, that only gives you Medium-Low Confidence. If this idea is a top customer request, or has come up in dozens of interviews, you assign the idea Medium Confidence.

Why so low? There are several important reasons to look at.

Wants vs. Needs

During my time at Gmail we repeatedly received requests from users in “emerging markets” (South Asia, South America, Africa) to add an option to “log out” of the Gmail Android app. This request didn’t make sense to us as all Google apps as well as Android subsystems share that same Google user account. Logging out of Gmail would be like logging out of your phone. Only after we interviewed users did we understand the reason for the request. In many countries a single phone may be shared by family members, so It’s understandable that you would like to “log out” from your email app to prevent family members from reading your personal communication.

This story is typical of user requests. The users may ask for a specific solution that they believe will best address their needs, but they’re not in a good position to know if it really will. They also are unaware of the consequences of their idea (like disabling most of the OS), and of the alternatives. Naively following customer requests can therefore lead us to a very suboptimal solution.

The better approach is to first understand the underlying need, and only then consider solutions (if we deem this need important). Sometimes we discover we already have a solution in place. This was the case in the “log out” issue: Android comes with built-in support for multiple users on a single device that addresses the privacy issues and does much more. So the right solution was to help users discover and use this feature.

Join 15,000 product people who receive my articles, tools, and templates in their inbox

Feedback Biases

User input is qualitative and susceptible to various biases:

- Loud vs. quiet users— I observed that both in b2c and b2b, the loudest and most persistent customers typically get a disproportionate share of the attention. At Google I saw power users driving esoteric problems (“when I run this complicated search query, the results aren’t perfectly correct”) to the top of the feedback charts by sheer perseverance. In B2B, the most demanding customers may get access to the CEO or CPO, and thus influence the thinking of the company. In contrast, the majority user that is quieter, may be underrepresented in customer feedback.

- Selection biases — The sample of users/customers we pick for surveys and interviews may skew the results (true also for other tests).

- Small samples — If we speak to, say, three customers, and all three make the same request (e.g. integrate an AI chatbot), our minds will automatically assume that we found a broad trend. But this can just be a random pattern in the noise, or just a momentary buzz. That’s why anecdotal evidence is so weak.

- Interpretation biases – Our interpretation of what the customers are saying may reflect our beliefs and values.

Incremental vs. Transformational

Customers’ frame of reference is the product as it is now and perhaps similar products they know. The suggestions therefore tend to be incremental — additions or modifications rather than step-functions. In fact, customer feedback may sway you against big transformational changes. Consider the case of business smartphones. For a long time enterprise customers demanded multi-day battery life and a physical keyboard, which the incumbents — Blackberry, Nokia, and Microsoft — considered must-haves. And yet multi-touch smartphones that came with neither took over the market in a few short years. The lesson is that it’s not for the customers to envision the next big thing, it’s for us.

What They Say vs. What They Do

Ever bought a product just because of this one feature that you felt you simply must have (TV with High Dynamic Range, smartwatch that measures blood oxygen saturation), only to never use it? Your customers can do the same with the features and capabilities they demand. These are common reasons for this mismatch:

- Bad at predicting their own future behavior — while a feature may seem important in theory, until they get it and try to use it, the customers won’t know how useful it is to them, and whether it fits in their environment and workflows.

- Future-proofing —customers may ask for things they think they’ll need in the future, but are not planning to use in the short term (but they’ll never tell you this unless you ask.)

- Backwards compatibility — This feature existed in a past product, and while no one really needs it, it feels like a step back not to have it.

- A checklist item— The customer may create (sometimes by committee or based on articles and reviews) an exhaustive list of everything they think they might need, which sometimes comes as a Request for Proposals (RFP). Naturally not everything on the list is important or even necessary, but these priorities are rarely communicated.

Not All Risks Covered

Using Cagan’s four risks model, we can see that customer requests may show demand (ie potential Value) for an idea, but tell us nothing about feasibility, usability, or business viability. It’s important to consider these other risks as well before choosing an idea to build.

Respect What They Say but Validate

None of this is to say that all customer requests are unimportant or disconnected from reality. Nor should you adopt the adage attributed to Henry Ford: “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses” (which he probably never said.) We should respect what the customers are saying, but be cognizant of the differences between speech and action.

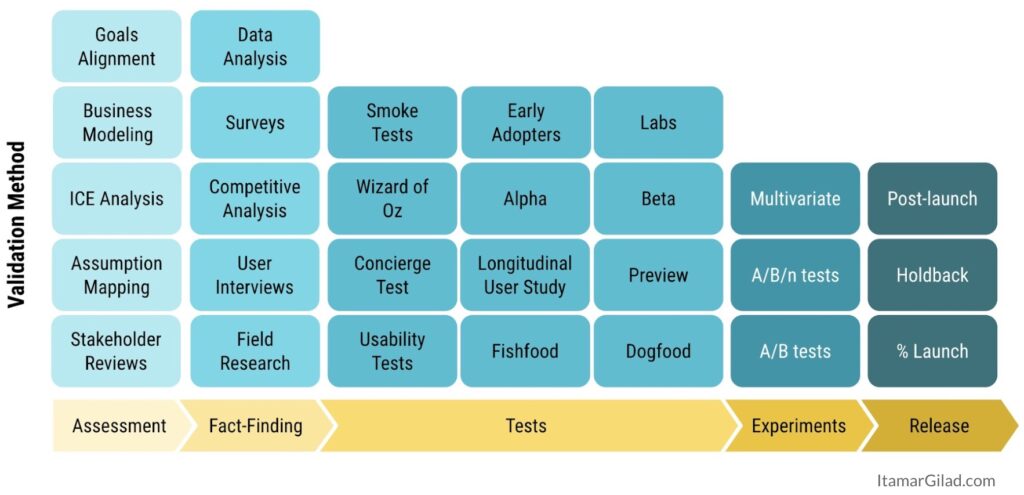

It’s for that reason that modern product development strives to validate product ideas by testing their core assumptions with customers. This process of product discovery is described in many articles and books, including my own, Evidence-Guided, where I discuss the wide gamut of validation techniques available to us irrespective of customer type and industry:

Customer Feedback — Important but Not Sufficient

When I started working as a product manager in the early 2000s the best practice was to collect customer requests, cross them with stakeholder and manager opinions, and come up with a roadmap. We considered the features we picked largely “validated” and didn’t bother to test them in anything but a last-minute beta. Many companies (especially b2b) still practice this approach today (perhaps with some newer terms like MVP instead of beta). However in the 2020s this form of product management should be recognized for what it is: lazy reactive and ineffective.

If you’re prioritizing ideas or developing a product to help with prioritization, consider these suggestions: 1) factor in multiple forms of evidence besides what the customers say, and 2) reflect the important concept of Confidence levels that are based on the strength of the evidence. Doing this will greatly improve your ability to pick the right ideas to build, and help you avoid delegating product decisions to the customers.

In my courses we practice implementing evidence-guided development and empowered teams hands-on.

Secure your ticket for the next public workshop or contact me to organize an in-house workshop or keynote for your team.

Cover image by cottonbro studio