It’s no secret that product management is often a misunderstood and misused role. Many companies restrict PMs to narrow, stereotypical jobs, hindering their potential impact. Without strong role models, some PMs fall victim to these product management myths and perpetuate them to new hires.

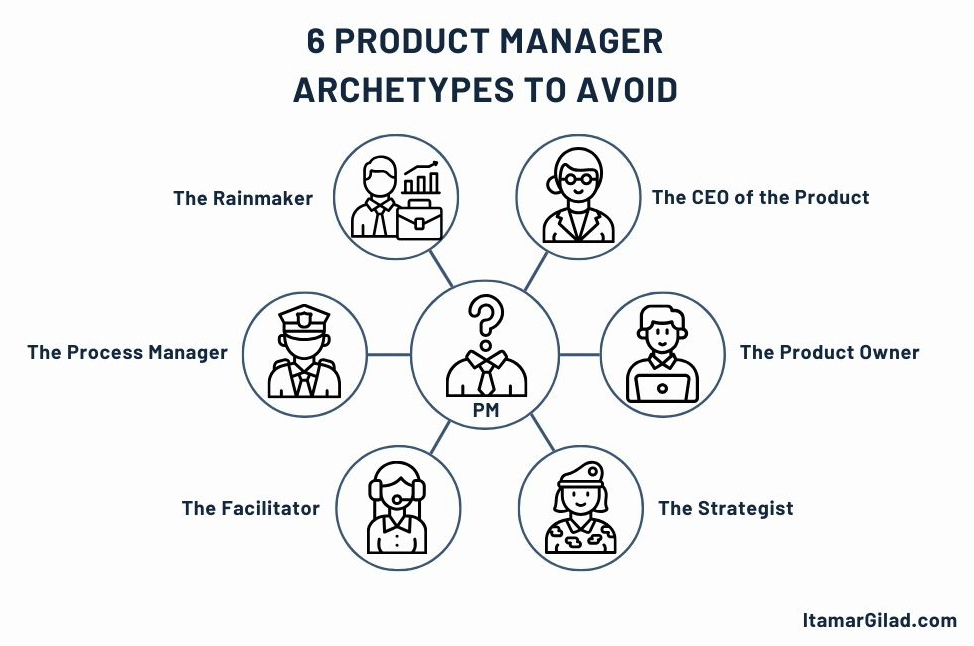

Here are six wrong ways to think about the product managers, and an alternative that I like.

The CEO of the product

This old chestnut is fading away, but I still come across PMs who believe it’s their job to tell the developers and designers what to do, and to control their time and quality of outputs. First, that’s not a CEO, that’s a 1920s assembly-line manager. Second, while a product manager is indeed a leadership role, the PM certainly should not try to manage the team. Good products are built through intense interdisciplinary collaboration. Having the PM call all the shots will result in weak product ideas, low team commitment (they’re there just to deliver), and a huge workload for the PM; not to mention that engineers and designers will resent a PM trying to manage them.

Better model: The Trio/Triad leadership model.

The Product Owner

This stereotype is typical of companies who adopted Scrum before they discovered Product Management (very common in Europe and Asia). A product owner has become a full-time role rather than a Scrum “hat”. The PO is there to serve the team and to maximize delivery. She translates the roadmap (created by others) into product backlogs, user stories, and epics. She’s expected to participate in all the ceremonies, but not to develop user and market expertise (that’s the job of the Strategist — see below). It’s a very laborious and joyless role that contributes to output, but rarely to outcomes.

Better alternatives: full-featured PM that works closely with the team, but with far less Agile dev overhead, which leaves time to focus on the users, market, and business.

The Strategist

This is the missing half of the PO, a mid-level PM solely responsible for thinking of the “big picture”, looking at the users, business and market, talking to managers and stakeholders (see the Facilitator below) and devising the perfect roadmap. However no PM, senior has she may be, can do a good job without having tactical understanding of the software and the team. Handing off features to someone else to figure out the “small details” has never worked. Product development requires many iterations and changes. Splitting the decisions across two people makes everything slower and less effective.

Better model: PMs at all levels should do both outbound (customer/market-facing) and inbound (team/product-facing) work. They should think both tactically and strategically. With seniority, the strategic, operational, and political parts grow, but being in the details and knowing the people that do the work is a must-have for any PM no matter her rank.

The Facilitator

This person’s job is to run between managers, stakeholders, and team, collect everyone’s product ideas, then mediate some compromise. In practice good products are never “discovered” through consensus, so this is a massive waste of PM talent. The facilitator PM is powerless to make decisions, even if she understands the users, market, product and the business very well. Her ability to create a positive impact is very limited.

Better model: Facilitate agreed-upon outcome goals with managers and stakeholders, then empower each part of the org to find ways to achieve these goals (see the GIST model, explained in detail in my book Evidence-Guided).

The Process Manager

Whether it’s OKR, OST, SAFe, GIST, or the various Agile and launch processes, PMs are often expected to make it all happen. Managing the processes-of-the-day, ones they had no part in choosing, creates a ton of work for PMs (Jira tickets anyone?). Accumulation of frameworks and methodologies can easily overwhelm and distract the product org, and especially the PMs. Ultimately —and I’m saying this as someone who creates frameworks for a living — implementing a process is output, and one that doesn’t necessarily lead to outcomes.

Better alternative: It’s much better if PMs, and more broadly, product trios, are charged with achieving better product development outcomes, while being allowed to be flexible in how to implement the processes.

Join 15,000 product people who receive my articles, tools, and templates in their inbox

The Rainmaker

For this type of PM, serving the business is the one and only goal. Success is measured in terms of revenue, profit, and number of paying customers. User needs and value-to-user are foreign concepts. The customers are the source of money and the market is territory to capture. These PMs are unable to think of anything except deal-closing/revenue-generating features (hey, let’s run another promo!). The rainmakers are blind to the most powerful lever they hold to help the business — creating high-value products. Thus, they’re often the least creative PMs of the bunch.

Better alternative: guide PMs, and more broadly product teams, to focus on both value delivered and value captured, measured by the North Star Metric, Top Business Metric and their submetrics.

The Alternative: The Full-Stack PM

While each of these stereotypes is wrong in its own way, they all contain large grains of truth. Product managers are indeed leaders and go-tos for product matters, but not CEOs. They support their teams in the delivery phase, but that’s not the sum total of their role (there’s also strategy, research, and discovery). They understand the bigger picture, but they don’t throw features over the wall for some low-level PM/PO to deliver. PMs listen to managers, stakeholders and team, but don’t base decisions solely off these inputs. They are key drivers of processes (and often introduce better ones), but only as a means to an end. PMs build things that help the business, but always with deep focus on the users and customers. If you’re able to do all of the above, you’re a full-stack PM.

If this PM job description sounds too good to be true, it may be that you haven’t worked for the right company yet. One-dimensional PM roles are a reflection of the beliefs and culture of the organization, which is why the job changes so much from company to company. But I find these stereotypes are also persisted by the PMs themselves. If you want to be treated as a full-stack PM my advice is to start thinking and acting like one. Believing in your abilities, and adopting better practices can help you break the stereotypes or lead you to a place where PMs are better understood and appreciated.

In my workshops we practice implementing evidence-guided development and empowered teams hands-on.

Secure your ticket for the next public workshop or contact me to organize an in-house workshop or keynote for your team.