As I’m writing this, the dreaded yearly planning cycle is just around the corner and the debate over roadmaps is surfacing once more. On one hand it’s clear that classic roadmaps that show releases on a timeline create both high planning overhead and high waste. On the other hand, attempts to construct roadmaps around outcomes and themes (often with no timeline) may leave the organization wanting. Classic roadmaps come with a big promise: they allow you to plan resources, track progress, and coordinate launches. While they don’t really deliver, the desire to have these things isn’t likely to go away.

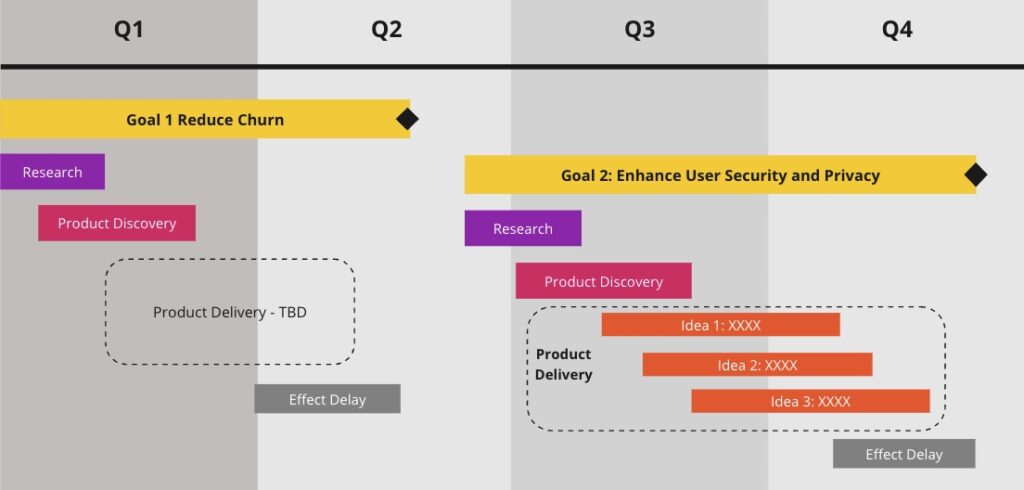

So what if we try to combine both worlds — an outcomes roadmap that shows the real work that goes into achieving the goals, on a timeline. Such a roadmap can create effectively communicate the things most roadmaps omit, while stressing the point that the plan has to be adapted as new information emerges.

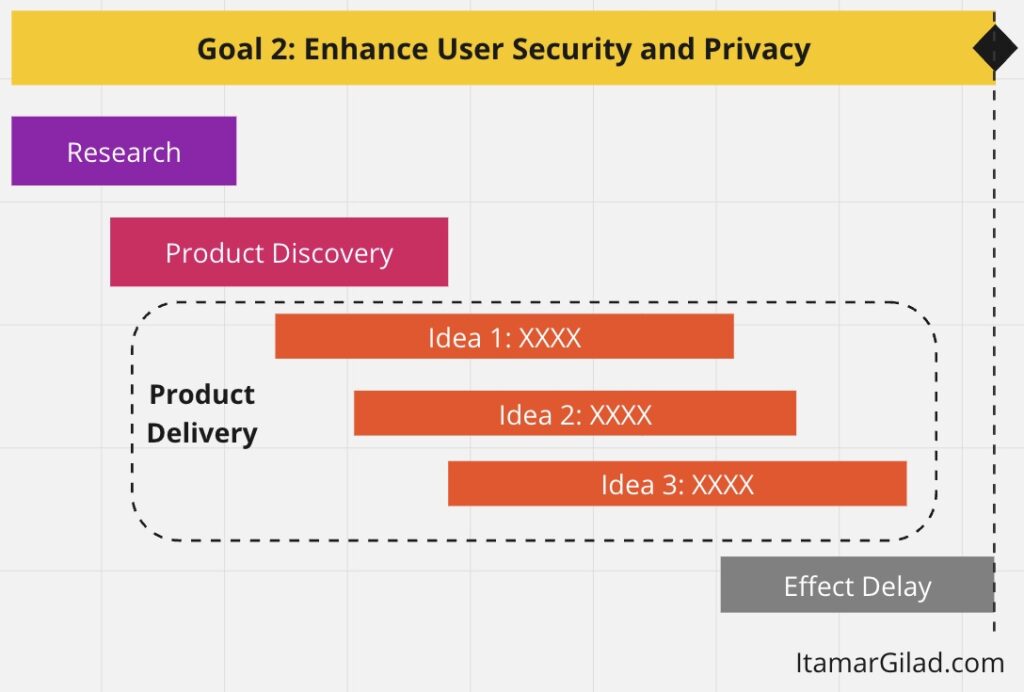

The elements of this roadmap are:

- Goals

- Research (optional)

- Product Discovery

- Product Delivery

- Effect Delay

Here’s what such a roadmap might look like for a single goal.

And here’s a Miro Outcome Roadmap template you can copy.

Let’s take a closer look at each element of the roadmap.

Goals

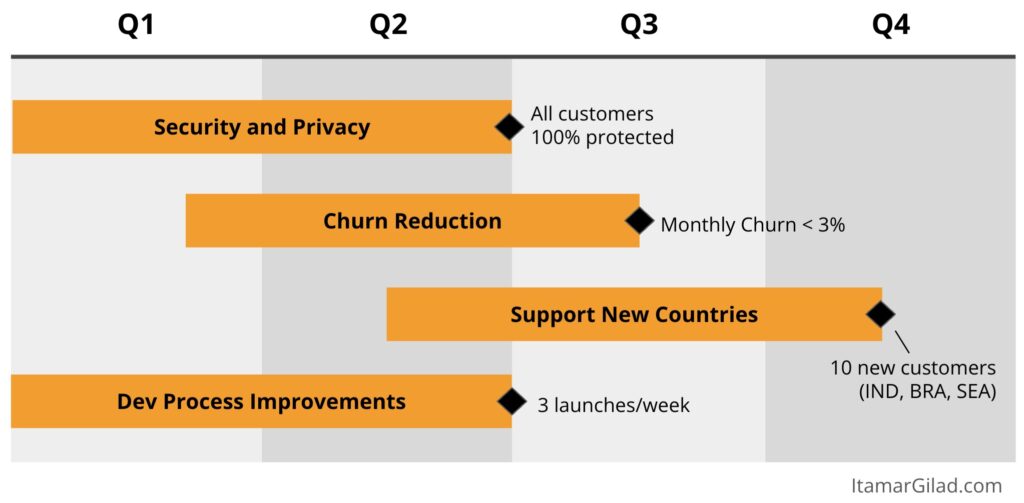

One glaring omission in most output roadmaps is that there are no goals anywhere to be seen. It’s all output, no outcomes. A good starting point therefore is to try to plot the company’s goals on a timeline.

If you’re familiar with Objectives and Key Results this diagram should be fairly easy to understand. The four bars represent the company’s 4 yearly objectives, somewhat abbreviated. The diamond denotes when the goal will be achieved, and we add one or more key results that indicate what success is. I listed just one for simplicity, but the OKR doc may include more.

Laying out your goals on a timeline like this already helps us assess if we’re being ambitious-yet-realistic. Experienced CTOs can sense from such an image whether the dev org is going to be overstretched. Naturally these are very rough guesses that you’ll have to adjust as you move forward, just like with any plan.

You could stop at this level, and in some cases that’s enough structure to get going. But if you want to have more planning clarity, you can zoom into each of the goals and plan the work needed to achieve it.

Research and Ideation

The first step in achieving a goal is asking whether we understand the context enough to do meaningful work. The context can include customers’ needs, applicable technologies, competitive/partner landscape, challenges and opportunities, and more. For example if we wish to reduce churn, do we know what’s causing customers to churn? If we wish to launch our product in new countries, do we know which country presents the best opportunity?

It’s tempting to answer such questions with a Yes. Customers are churning because we lack features A, B, and C. The best country to launch next is India because there’s a massive demand for our type of product. But then, you have to be honest and ask the next question: how sure are we about these assumptions? Or in other words, what’s the evidence?

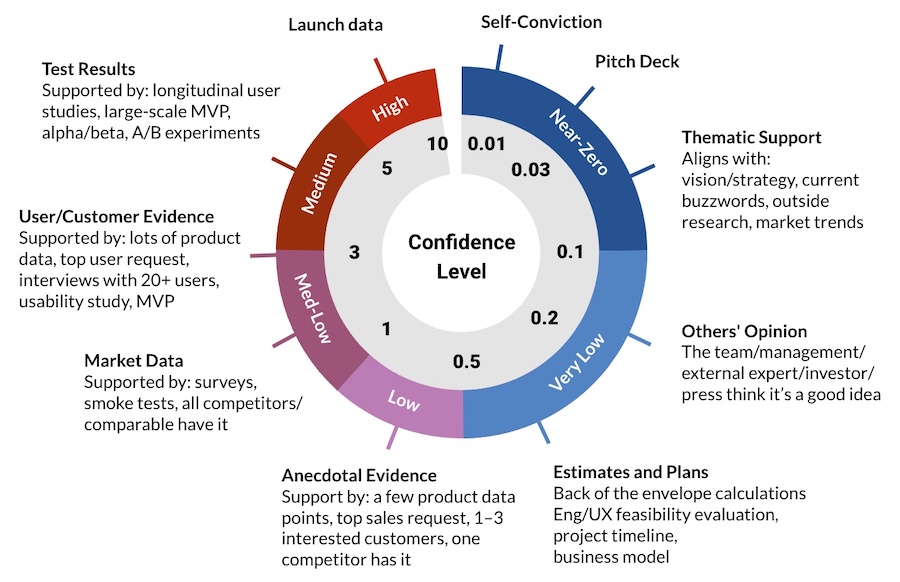

Here the Confidence Meter can help you calibrate:

If your conviction comes from opinions, themes, or anecdotal evidence you should have low confidence in your assumptions. In this case it’s best to spend some time on research, known also as exploratory or generative research and bring the level of confidence to medium-low or medium.

There are multiple flavors of research: user research, market research, competitive research, technology research, and so on. You need to decide what kind of research to conduct and then budget time and resources for it.

Research isn’t a bad word — an ounce of research can save you a ton of wasted work down the road chasing opportunities that don’t exist. The outcomes of the research phase have to be clear: insights and opportunities backed by medium-low to medium evidence.

Research often leads to ideation — coming up with potential ways to achieve the goal. Other ideas will come outside of your research — from customers, managers, stakeholders, and team members. This all is normal and healthy. We should collect all of the ideas we find as input for the next phase.

Join 15,000 product people who receive my articles, tools, and templates in their inbox

Product Discovery

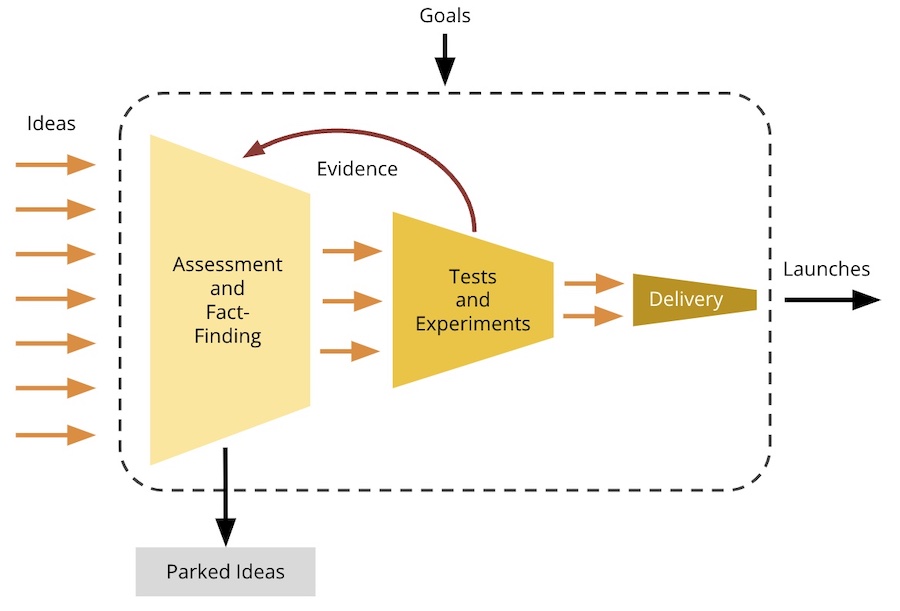

Once we have a good understanding of the context and an initial set of ideas, we can dive into product discovery. Product discovery (a term defined by Marty Cagan) is a broad topic covered by many authors, and the key theme of my book Evidence-Guided. In short, in product discovery we evaluate and validate multiple ideas against the goal, parking the ones that don’t work and doubling-down on the ones that do.

The outcome of product discovery is a small set of ideas that are sufficiently validated to move into delivery. I’m often asked how long you should spend in discovery, and the answer is as long as it takes, because cutting it short may lead to building the wrong things. However you may wish to timebox your discovery work with the understanding that if you haven’t found any validated ideas within say, 4 weeks, you’ll switch to another goal or revert to research to find more ideas.

Product Delivery

Once we discover an idea that can contribute to the goal, the next step is to build and launch it. If we’re lucky one idea will achieve the entire goal, but often we’ll need more than one. Most ideas that have gone through product discovery are already partially developed, and you should have a much better understanding of how much time and effort they will take to complete .

Note that this part of the roadmap is equivalent to the classic roadmap — a series of projects with concrete launches on a timeline. Alas, without research and product discovery we cannot predict which ideas these will be and how long they will take to develop. So starting with this part of the roadmap is a definite no-no.

In my courses we practice hands-on how to replace roadmaps and project plans with adaptive planning.

Secure your ticket for the next public workshop or contact me to organize an in-house workshop for your team.

Effect Delay

The outcomes you’re trying to achieve (for example higher customer retention rate) often don’t appear immediately post-launch; There’s usually some delay due to deployment timing, sales/marketing timing, adoption lag, etc. When we’re building a roadmap for outcomes rather than launches we should factor for these delays too. The product team is usually free to work on other things during this time, but we should keep tracking the results even after the launch.

Here’s what two goals look like side-by-side with the product delivery part still marked as To-Be-Determined (left) and flashed-out with 3 ideas (right):

Advanced techniques: Here are some ideas from roadmap experts. Janna Bastow, CEO and co-founder of ProdPad, recommends the soft-launch model where the product change is first “launched” to sales and marketing, which then prepare for the actual launch. Another model is to launch the changes, but then plan for post-launch “tweaking” to optimize the changes and improve the results (source: Bruce McCarthy, author of Product Roadmaps Relaunched) — essentially launch-and-iterate, but with the “iterate” part being budgeted for in the roadmap.

Here’s is the full Outcome Roadmap template (Miro Board) which you can use as a basis.

Conclusion

I don’t necessarily recommend that you use this roadmap format, but if your managers and stakeholders insist on having a work plan along a timeline it may be useful to pull it out and hold a discussion. Key points to address:

- Are we aiming for outcomes or for launches?

- Can we be certain that we found the right ideas without research and product discovery?

- Are research and product discovery contributing to the business goals (I argue they do)

- Is this model slower? In what sense: time-to-bits-in production or time-to-outcome?

This discussion will go to the heart of the disagreement on output roadmaps, but hopefully you’ll be better armed to make your case. The goal isn’t to push back against planning, but to make the planning honest and adaptive.