Idea prioritization exercises are often hard and unsatisfying. The discussions run long and the decisions feel suboptimal. Using numeric methods like ICE or RICE adds more process, but not necessarily more clarity, as the numbers feel “made up”. I’ve written in the past about how to make better use of ICE, but I have to tell you that that’s just one piece in much a larger puzzle. Good idea prioritization requires a few key fundamentals that many companies lack.

Let’s look at these missing parts one at a time.

Strategic Context

Prioritization goes broader and deeper than a list of ideas in a bank. It starts with the following:

- A mission — The mission is the top objective of the company. It answers the questions: What is this company about? What long-term positive change are we trying to bring about? How are we going to create value and for whom? Examples: “Organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful” (Google), “Connect the world’s professionals” (LinkedIn), “Spread Ideas” (TED). The mission is a very broad exercise in prioritization: We’re going to deliver this type of value for these customers, and nothing more.

- A Strategy — A strategy is an evolving theory on how we will accomplish the mission. Specifically the strategy should explain which strategic opportunities we’re going after, which threats we need to mitigate, what are our principles of operation (for example “prioritize Seller needs first”), and other guidelines that will help drive decisions and cohesion across the board. Forming a strategy takes much more time and effort than a 2-day offsite. It’s an ongoing voyage of research, discovery and iteration, and it includes saying No to a great many opportunities and shiny objects.

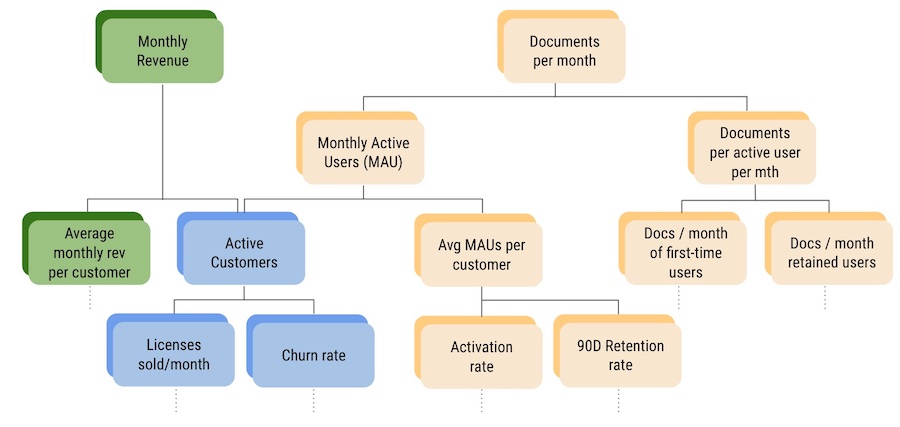

- A growth model — To make things concrete we should make the success of our mission and our strategy measurable. It’s very useful to have a model that points at the most important top-level metrics and connects those into lower-level metrics we can more readily influence. One such model that I often recommend is the Value-exchange-Loop, which comes with two top metrics: the North star metric, and Top Business Metric. I then suggest creating a metric tree below each one (see this article, or my book for details).

We learn how to create better missions, strategies, metrics trees, and goals, as well as how to discover and deliver the right products in my workshops: itamargilad.com/workshops

Concise, Measurable Goals

The point of prioritization exercises is to determine which ideas are most likely to contribute to the goals (Impact). To estimate impact we need goals that are tied to clear metrics that we can measure. For example: “we estimate the chatbot idea will have an impact of 8 out of 10 on the ratio of support cases resolved within 2hrs”. We want the goals to also be concise, i.e. have the minimal number of target metrics (or key results), because for each additional metric we’ll have to collect and prioritize ideas separately.

Measurable, concise goals are actually something of a rarity in product companies. Here’s what’s required:

- Company-Level Goals — Company leaders need to pick the most important achievements this year: 3-4 objectives with 2-3 KRs each (very large companies may have more). Every OKR added to at company-level is one more that every team needs to process and ask “what does it mean in our area of responsibility?” and “With whom do we need to collaborate with to achieve them?”. Having fewer goals drives focus and alignment, and increases the likelihood of success.

- Team-level goals – A product team of 12 people or less should work on no more than 3-4 key results per quarter, and these key results need to be measurable and realistic. Output goals — Do activity X, Launch feature Y — should not be included.

In large companies there may be more levels of goals in the middle, but every layer will add more overhead, so in general, having fewer goals is better. The good news is that the mission, strategy, and growth model give you most of what you need to construct good, concise and measurable goals. The strategy and top metrics will inform company-level goals. Company-level goals and the metrics trees will help teams create their own concise and measurable goals.

If you have strategic context and good goals in place, you’re already doing better than most. But there’s yet another element without which prioritization becomes hard and ineffective.

Product Discovery

What’s the goal of your idea prioritization? If the answer is “to decide which ideas to build in full and launch” then you’re facing a very high commitment decision—if we choose idea A, we have to let go of ideas B, C, and D. Often (and understandably) managers will not be willing to delegate so much power. If you do get to make the decision, you should expect high pressure and politics — everyone will be pushing hard for their idea. Even worse, the decision is often made based on bits of evidence, opinions, and gut instinct, hence the ICE numbers look made up.

A better purpose for idea prioritization is to answer the question “which ideas should we test first?” This greatly lowers the stakes and also allows more ideas to make the cut as we’re not committing to build them in full. As nobel-prize winner Linus Pauling observed: “If you want to have good ideas you must have many ideas. Most of them will be wrong, and what you have to learn is which ones to throw away.”

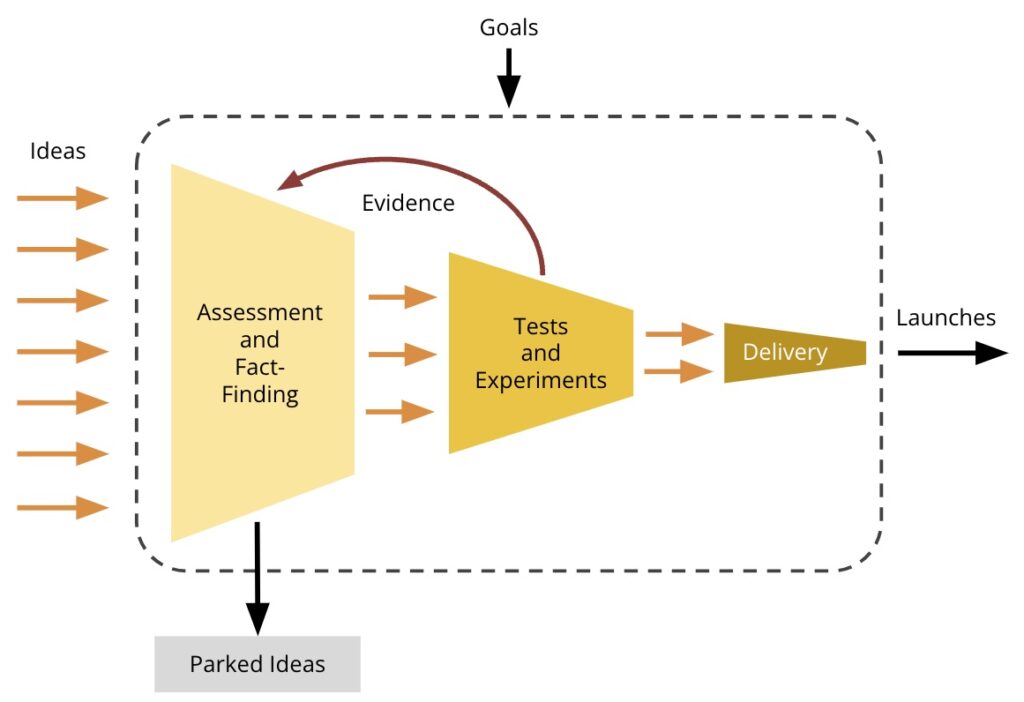

Consider prioritization an ongoing process (rather than something you do once a quarter). It has two parts:

- Idea Evaluation – we evaluate the ideas using ICE or RICE based on the available evidence we have

- Idea Validation – we build versions of the ideas and test them, thus generating new evidence.

The two together form your Product Discovery loop which then leads to product delivery.

Are You Doomed?

Reading through this article you may conclude that you simply cannot prioritize in your current state, either because your company is lacking strategic context and clear and concise goals, or because your team and org don’t value product discovery. Indeed many companies suffer from one or both of these issues. In my courses people report having these challenges again and again.

What can you do? If you can, try and improve things in your area of responsibility, whether it’s a team, a group, or an entire sub-org. Attempt to create a mission for this area, identify key metrics, and create measurable and concise goals. Try to also change the definition of prioritization to “what should we test first”, and use evidence to back your decisions.

More broadly you may wish to educate and inform managers, peers and reports (for example by sharing this article), and shine a light on what’s missing. Be warned that It may be a very big and complex undertaking. In my book, Evidence-Guided, I’m proposing a model called GIST — Goals, Ideas, Steps, Tasks, that I’ve found to help. The key point, as always, is to take an active part. Don’t wait for the change to happen around you, as you may have to wait for a very long time.

Join 15,000 product people who receive my articles, tools, and templates in their inbox